|

| Aristotle Pop Art |

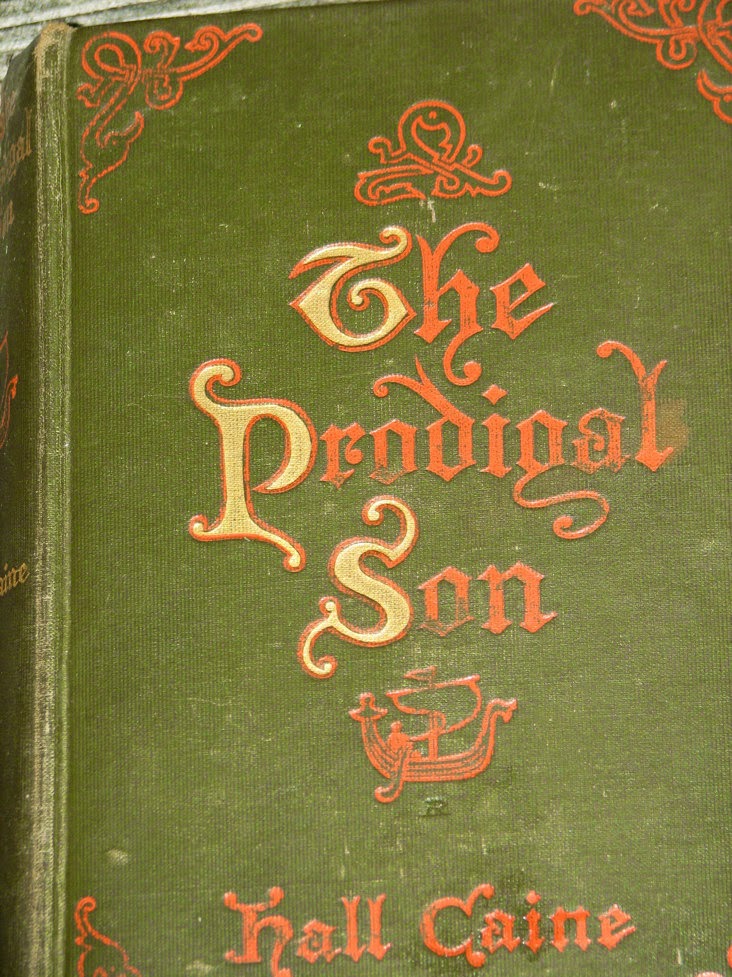

Today, I share, for your reading pleasure, Oscar Wilde’s “Aristotle at Afternoon Tea,” a review of J.P. Mahaffy’s “Principles of the Art of Conversation,” which Wilde calls “the nearest approach, that we know of, in modern literature to meeting Aristotle at an afternoon tea.” It was first published in the Pall Mall Gazette, 16 December 1887.

|

| The Importance of Being Earnest (1952) movie |

Aristotle at Afternoon Tea

by Oscar Wilde

In society, says Mr. Mahaffy, every civilised man and woman ought to feel it their duty to say something, even when there is hardly anything to be said, and, in order to encourage this delightful art of brilliant chatter, he has published a social guide without which no débutante or dandy should ever dream of going out to dine. Not that Mr. Mahaffy's book can be said to be, in any sense of the word, popular. In discussing this important subject of conversation, he has not merely followed the scientific method of Aristotle which is, perhaps, excusable, but he has adopted the literary style of Aristotle for which no excuse is possible. There is, also, hardly a single anecdote, hardly a single illustration, and the reader is left to put the professor's abstract rules into practice, without either the examples or the warnings of history to encourage or to dissuade him in his reckless career. Still, the book can be warmly recommended to all who propose to substitute the vice of verbosity for the stupidity of silence. It fascinates in spite of its form and pleases in spite of its pedantry, and is the nearest approach, that we know of, in modern literature to meeting Aristotle at an afternoon tea.

As regards physical conditions, the only one that is considered by Mr. Mahaffy as being absolutely essential to a good conversationalist, is the possession of a musical voice. Some learned writers have been of opinion that a slight stammer often gives peculiar zest to conversation, but Mr. Mahaffy rejects this view and is extremely severe on every eccentricity from a native brogue to an artificial catchword. With his remarks on the latter point, the meaningless repetition of phrases, we entirely agree. Nothing can be more irritating than the scientific person who is always saying "Exactly so," or the common-place person who ends every sentence with "Don't you know?" or the pseudo-artistic person who murmurs "Charming, charming," on the smallest provocation. It is, however, with the mental and moral qualifications for conversation that Mr. Mahaffy specially deals. Knowledge he, naturally, regards as an absolute essential, for, as he most justly observes, "an ignorant man is seldom agreeable, except as a butt." Upon the other hand, strict accuracy should be avoided. "Even a consummate liar," says Mr. Mahaffy, is a better ingredient in a company than the scrupulously truthful man, who weighs every statement, questions every fact, and corrects every inaccuracy." The liar at any rate recognises that recreation, not instruction, is the aim of conversation, and is a far more civilised being than the blockhead who loudly expresses his disbelief in a story which is told simply for the amusement of the company. Mr. Mahaffy, however, makes an exception in favour of the eminent specialist and tells us that intelligent questions addressed to an astronomer, or a pure mathematician, will elicit many curious facts which will pleasantly beguile the time. Here, in the interest of Society, we feel bound to enter a formal protest. Nobody, even in the provinces, should ever be allowed to ask an intelligent question about pure mathematics across a dining-table. A question of this kind is quite as bad as enquiring suddenly about the state of a man's soul, a sort of coup which, as Mr. Mahaffy remarks elsewhere, "many pious people have actually thought a decent introduction to a conversation.”

As for the moral qualifications of a good talker, Mr. Mahaffy, following the example of his great master, warns us against any disproportionate excess of virtue. Modesty, for instance, may easily become a social vice, and to be continually apologising for one's ignorance or stupidity is a grave injury to conversation, for, "what we want to learn from each member is his free opinion on the subject in hand, not his own estimate of the value of that opinion." Simplicity, too, is not without its dangers. The enfant terrible, with his shameless love of truth, the raw country-bred girl who always says what she means, and the plain, blunt man who makes a point of speaking his mind on every possible occasion, without ever considering whether he has a mind at all, are the fatal examples of what simplicity leads to. Shyness may be a form of vanity, and reserve a development of pride, and as for sympathy, what can be more detestable than the man, or woman, who insists on agreeing with everybody, and so makes "a discussion, which implies differences in opinion," absolutely impossible? Even the unselfish listener is apt to become a bore.

"These silent people," says Mr. Mahaffy, "not only take all they can get in Society for nothing, but they take it without the smallest gratitude, and have the audacity afterwards to censure those who have laboured for their amusement." Tact, which is an exquisite sense of the symmetry of things, is, according to Mr. Mahaffy, the highest and best of all the moral conditions for conversation. The man of tact, he most wisely remarks, "will instinctively avoid jokes about Blue Beard" in the company of a woman who is a man's third wife; he will never be guilty of talking like a book, but will rather avoid too careful an attention to grammar and the rounding of periods; he will cultivate the art of graceful interruption, so as to prevent a subject being worn threadbare by the aged or the inexperienced; and should he be desirous of telling a story, he will look round and consider each member of the party, and if there be a single stranger present will forgo the pleasure of anecdotage rather than make the social mistake of hurting even one of the guests. As for prepared or premeditated art, Mr. Mahaffy has a great contempt for it and tells us of a certain college don (let us hope not at Oxford or Cambridge) who always carried a jest-book in his pocket and had to refer to it when he wished to make a repartee. Great wits, too, are often very cruel, and great humourists often very vulgar, so it will be better to try and "make good conversation without any large help from these brilliant but dangerous gifts.”

In a tête-à-tête one should talk about persons, and in general Society about things. The state of the weather is always an excusable exordium, but it is convenient to have a paradox or heresy on the subject always ready so as to direct the conversation into other channels. Really domestic people are almost invariably bad talkers as their very virtues in home life have dulled their interest in outer things. The very best mothers will insist on chattering of their babies and prattling about infant education. In fact, most women do not take sufficient interest in politics, just as most men are deficient in general reading. Still, anybody can be made to talk, except the very obstinate, and even a commercial traveller may be drawn out and become quite interesting. As for Society small talk, it is impossible, Mr. Mahaffy tells us, for any sound theory of conversation to depreciate gossip, "which is perhaps the main factor in agreeable talk throughout Society." The retailing of small personal points about great people always gives pleasure, and if one is not fortunate enough to be an Arctic traveller or an escaped Nihilist, the best thing one can do is to relate some anecdote of "Prince Bismarck, or King Victor Emmanuel, or Mr. Gladstone." In the case of meeting a genius and a duke at dinner, the good talker will try to raise himself to the level of the former and to bring the latter down to his own level. To succeed among one's social superiors one must have no hesitation in contradicting them. Indeed, one should make bold criticisms and introduce a bright and free tone into a Society whose grandeur and extreme respectability make it, Mr. Mahaffy remarks, as pathetically as inaccurately, "perhaps somewhat dull." The best conversationalists are those whose ancestors have been bilingual, like the French and Irish, but the art of conversation is really within the reach of almost every one, except those who are morbidly truthful, or whose high moral worth requires to be sustained by a permanent gravity of demeanour and a general dulness of mind.

These are the broad principles contained in Mr. Mahaffy's clever little book, and many of them will, no doubt, commend themselves to our readers. The maxim, "If you find the company dull, blame yourself," seems to us somewhat optimistic, and we have no sympathy at all with the professional story-teller who is really a great bore at a dinner-table; but Mr. Mahaffy is quite right in insisting that no bright social intercourse is possible without equality, and it is no objection to his book to say that it will not teach people how to talk cleverly. It is not logic that makes men reasonable, nor the science of ethics that makes men good, but it is always useful to analyse, to formularise and to investigate. The only thing to be regretted in the volume is the arid and jejune character of the style. If Mr. Mahaffy would only write as he talks, his book would be much pleasanter reading.

Follow me on Twitter @TinyApplePress and like the Facebook page for updates!

.jpg)

_1889,_May_23._Picture_by_W._and_D._Downey.jpg)

.jpg)

01b.jpg)

old7.jpg)